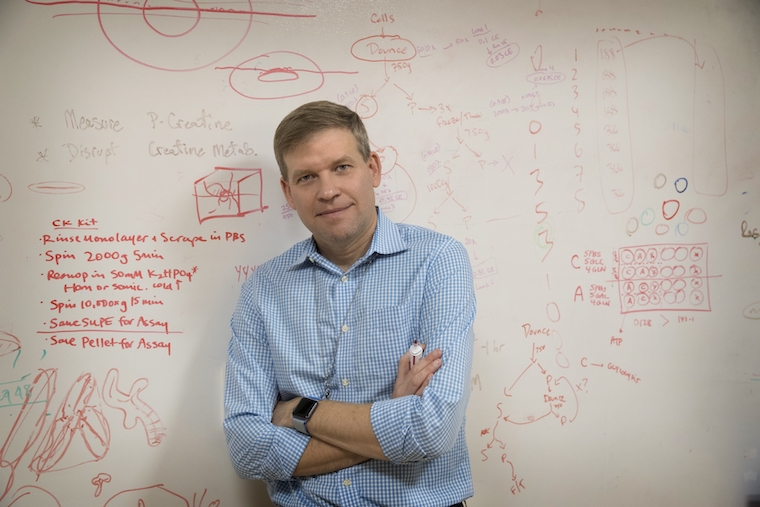

When our David Kashatus, PhD, was first interviewing here in 2012, he laid out an ambitious research project that would help us better understand pancreatic cancer. Seven years later, he has completed that work and given us important new insights into how the aggressive cancer fuels its growth. And, in so doing, he has helped answer a question that has bedeviled scientists for more than 80 years.

The counter-intuitive thing about cancers is that they rewire cells to be less efficient in how they fuel themselves. This is known as the Warburg Effect. Kashatus knew that there are strange changes in the shape of mitochondria, the powerhouses of cells, in cancers driven by mutations in the RAS gene. He wanted to understand what was occurring and how it affected pancreatic cancer’s growth.

He found that when the mutated RAS gene gets activated, it causes the mitochondria to fragment. This fragmentation supports the earliest shifts toward the cancer’s new fueling process. This was quite surprising, because suddenly the mitochondria were playing a bizarre role: Their division was actually helping the cancer take hold.

Blocking mitochondrial division in tumor samples largely prevented the tumors from growing, Kashatus found. And when they did grow, the cancer cells gradually lost mitochondrial function. This was bad for the cancer cells.

“This mitochondrial fragmentation is really playing two distinct roles: On the one hand, it’s promoting this shift in metabolism. But it’s also promoting mitochondrial health,” Kashatus said. “These two things are combining to drive the pancreatic tumor growth process. So I think this is something that could be therapeutically valuable. But it also really teaches us about pancreatic tumor growth in general.”

The finding also may help explain the workings of several drugs in development, and it could help doctors understand which patients they will benefit.

“Inhibiting [mitochondrial division in patients’ cancer cells] would be a nice future goal for us. However, the drugs targeting this process are really very early in development, and so it’s not something that will really be ready for the clinic anytime soon,” he said. “But this work can really help us understand how some of these other drugs that are a little bit further along in the process may be acting, so that we can better understand which patients may or may not benefit.”