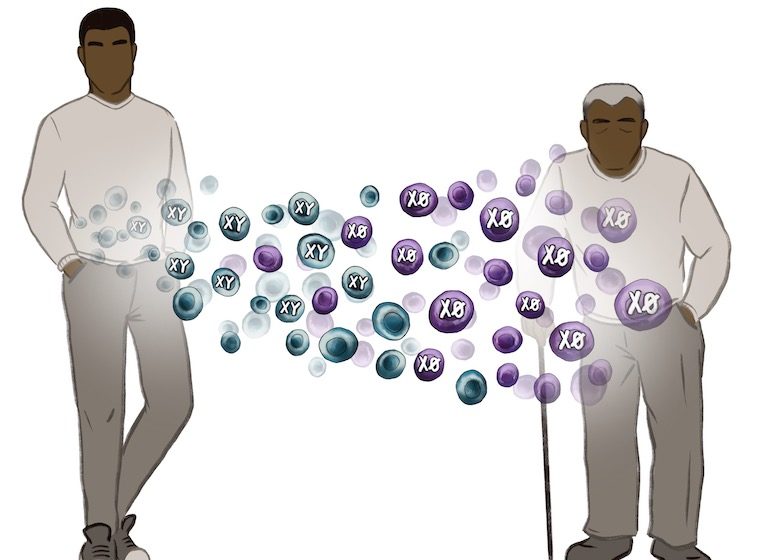

Approximately 40% of men will lose their male sex chromosome in certain cells by age 70, and that can cause scarring of the heart and lead to deadly heart failure, important new research by our Kenneth Walsh, PhD, reveals.

The new finding helps explain why women tend to live longer than men. Professor Walsh estimates that his discovery may explain four of the five-year difference in average lifespan in the United States.

“Particularly past age 60, men die more rapidly than women. It’s as if they biologically age more quickly,” said Walsh, the director of UVA’s Hematovascular Biology Center. “There are more than 160 million males in the United States alone. The years of life lost due to the survival disadvantage of maleness is staggering."

The Y chromosome loss occurs primarily in cells that turn over rapidly, such as blood cells. Scientists have known for years that this chromosome loss can occur, but Walsh's finding is believed to be the first hard evidence the loss has harmful effects on men's health. (The loss does not occur in male reproductive cells, so it's not inheritable; smoking, however, appears to put men at particular risk.)

Further, the effects are not limited to the heart. Instead, Y chromosome loss appears to trigger a harmful process called fibrosis (scarring) through the body.

The good news is that there is already a drug, pirfenidone, that Walsh believes could offer a potential treatment for the effects of Y chromosome loss. Pirfenidone has already been approved by the federal Food and Drug Administration for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, a form of lung scarring. The drug is also being tested as a treatment for heart failure and chronic kidney disease -- both of which exhibit tissue scarring.

Right now, there's no easy way for doctors to determine which men are suffering Y chromosome loss. But that could change: Professor Walsh is working with a collaborator, Lars A. Forsberg of Uppsala University in Sweden, who has developed an inexpensive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test, like those used for COVID-19 testing, that can detect Y chromosome loss. That test is largely confined to his and Walsh’s labs for now, but demand could help it spread: “If interest in this continues and it’s shown to have utility in terms of being prognostic for men’s disease and can lead to personalized therapy, maybe this becomes a routine diagnostic test,” Professor Walsh said.