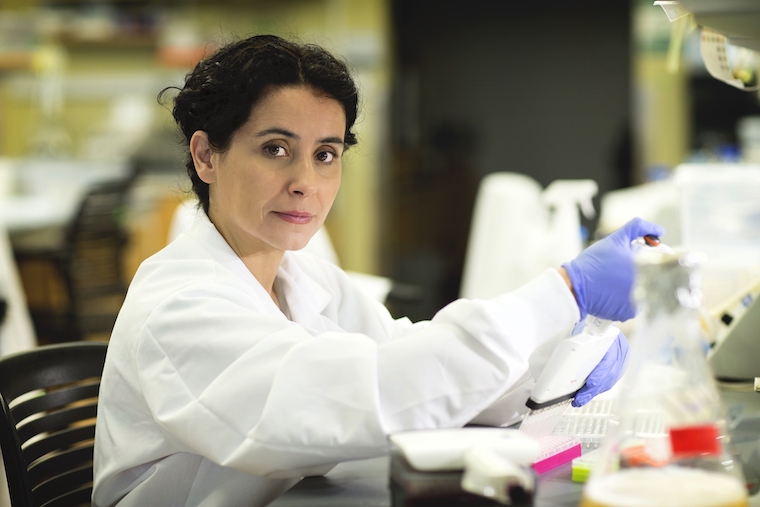

Our Eileen O'Rourke, PhD, and her collaborators have identified 14 genes that cause obesity, and targeting those genes could one day uncouple overeating from the harmful health effects of obesity.

Obesity, of course, is not just about our genes. We all know the importance of eating a healthy diet and getting more activity, so I won't belabor that point here. But our genes play a role in obesity, too. They help regulate how we store fat and affect how well our bodies burn food as fuel, for example. So if we can identify the genes that convert excessive food into fat, we can seek to inactivate them. That could have big health benefits.

The challenge is figuring out which genes to target. Scientists have found hundreds of genes that are associated with obesity, but it's not clear which ones cause obesity. O'Rourke and her colleagues wanted to identify the latter. So they enlisted the help of some tiny worms called C. elegans. Like us, these worms get fat if they eat too much sugar, and they share enough genetic similarity with us that they are useful for medical research. (In the last 20 years, three Nobel prizes went to discoveries of cellular processes first observed in worms but then found to be important in human diseases such as cancer and neurodegeneration. The worms have also been vital to the development of new treatments based on RNA technology.)

Professor O'Rourke and her collaborators used the worms to screen 293 genes associated with obesity in people. They developed a worm model of obesity, feeding some of the sugar-loving creatures a regular diet and others a diet loaded with fructose. This obesity model, coupled with automation and supervised machine learning-assisted testing, allowed the researchers to identify 14 genes that cause obesity and three that help prevent it.

Will these findings hold true in humans? The researchers say the indicators are encouraging. For example, blocking the effect of one of the genes in lab mice prevented weight gain, improved insulin sensitivity and lowered blood sugar levels -- just the sort of results we'd like to see in people.