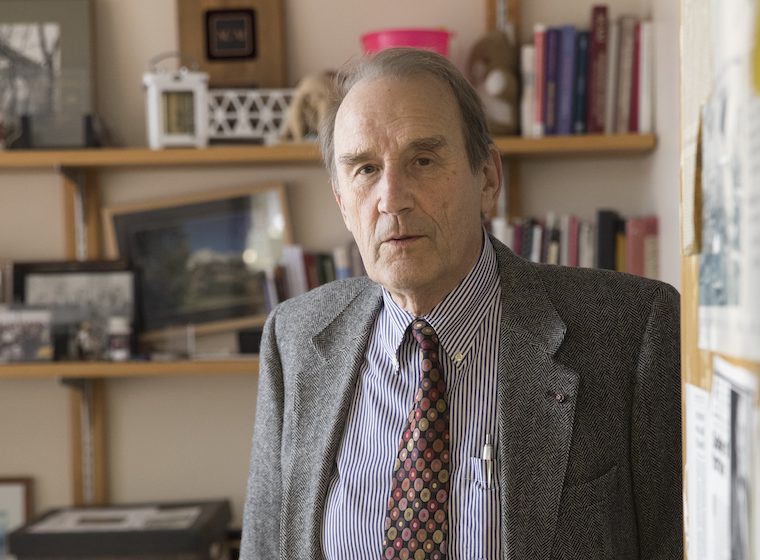

Our Thomas Platts-Mills discovered that tick bites can cause people to become allergic to red meat, a story that has fascinated people around the world. But that’s just one of his many accomplishments. UVA Today recently ran a very interesting profile on Dr. Platts-Mills, and the fine folks there have kindly allowed me to share this exclusive expanded version with you. Many thanks to Wes Hester, the author, and his colleagues.

It was on a trip to New Zealand with his father that Thomas Platts-Mills decided to be a doctor at the ripe old age of 9. There he met his grandmother, Dr. Daisy Platts-Mills, and came to understand the origin of his surname.

“Dr. Daisy Platts married Mr. Mills and said, ‘We will be Platts-Mills,’ and it’s lasted five generations now,” he explained in the genteel accent he acquired growing up in Colchester and London, noting that his is the oldest double-barrel name in the world created by a professional woman.

“She was such a powerful woman, and her daughter was tough, too,” he recalled, referring to Ada Platts-Mills, who was also a doctor. “I was very impressed, and by the end of that vacation, I was a doctor. I could tell you which college in Oxford I was going to go to and which medical school.”

Platts-Mills, now head of UVA’s Division of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, made good on those promises to himself, studying at Oxford’s Balliol College like his father and receiving his medical training at St. Thomas’ Hospital Medical School in London and earning his PhD from London University.

Now approaching his 50th year of research, Platts-Mills has become what his longtime colleague and friend Dr. Martin Chapman calls “a living legend” and “the most insightful clinical investigator of allergic diseases of his generation.”

His most recent acclaim has come from the now-famous discovery of a red meat allergy caused by tick bites. Since his article on the allergy was published in the New England Journal of Medicine, it has been cited more than 1,000 times and has been the subject of media attention across the globe.

His earlier work on dust mite allergens was also pivotal, shedding light on the association between mite allergies and asthma and highlighting early‐life allergen exposure as a risk factor for allergic diseases.

Chapman, who was a colleague at UVA from 1984-2001 and is now president and CEO of Charlottesville-based Indoor Biotechnologies, attributes much of Platts-Mills’ success to his “methodical approach” and his fearlessness.

“That has certainly been a feature of his work – to not be afraid to put yourself out there and take an idea that somebody else might reject instantly,” he said.

***

While Platts-Mills credits his grandmother with guiding him to medicine, his father’s influence was profound in shaping the way he approaches his work, and the world.

John Platts-Mills was a strident socialist who at various stages of his career worked as a criminal lawyer, a coal miner and a member of Parliament. After beginning his career in law, he joined the Labour Party and worked in politics for many years, at times finding himself ostracized for perceived communist sympathies. After working for Winston Churchill during World War II, he fell out of favor and was sent to work in the coal mines during the latter stages of the war, eventually emerging from the mines to be elected to Parliament in 1945.

After being expelled from the Labour Party and losing his seat in 1950, John Platts-Mills returned to his legal career and established himself as one of Britain’s top criminal barristers, representing high-profile clients such as the notorious gangsters the Kray twins and the Great Train Robbers. An obituary in The Telegraph called Platts-Mills “a master of courtroom theatre… [whose] clashes with the Bench entered into legal legend.”

Platts-Mills recalls those roller coaster years as being formative in his own outlook.

“If we thought B and the rest of the world thought A, that was formal proof that B is correct,” he said. “When we saw crazy things – when we saw things that didn’t make any sense – that was a reason to be interested, not to be afraid of it.”

That attitude has clearly shaped Platts-Mills as a person and a researcher. As colleagues and friends know, he has a mischievous sense of humor and enjoys playing the role of devil’s advocate – poking, prodding and challenging assumptions. And it has been the basis for his biggest scientific breakthroughs.

“The thing that has driven my career has been being willing to go off the deep end and be totally unafraid of pushing an idea that other people don’t believe,” he said. “Too many people are afraid of getting involved in an idea that’s too far away from normality.”

***

Platts-Mills found his focus and mentor in the 1970s as an allergy fellow at Johns Hopkins University, working for Dr. Kimishige Ishizaka, who had just discovered Immunoglobulin E, antibodies produced by the immune system in response to allergies.

“It was unbelievable. He taught me how to do science,” Platts Mills said of his time with Ishizaka. “He taught me more about the philosophy of science and how you work things out and how much you need to do before you move on.”

Platts-Mills returned to England and embarked on his groundbreaking dust mite work with Chapman, who was an undergraduate at the time and was offered a PhD position by Platts-Mills working on the purification of the house dust mite allergen.

After observing that patients at his clinic with asthma were sensitive to dust mites, Platts-Mills, Chapman and Dr. Juran Tovey worked to purify the allergen and ultimately discovered that mite feces were the source of the allergen.

The discover was transformative, explaining why allergic sensitization to mites was so strongly associated with asthma.

“We suddenly realized that the real way for an allergen to contribute to asthma was big particles, not small particles,” Platts-Mills said. “It was one of those occasions where we realized that everything had been wrong, and this was right.”

Platts-Mills was lured back to the states in 1982 as UVA’s Oscar Swineford Professor of Medicine and became head of the division in 1993, making him the longest serving head of division in Department of Medicine history.

“And I’ve not been promoted since and I’m very angry about it,” he joked.

***

Following his breakthrough in 2007, Platts-Mills has spent much of the last decade focused on the red meat allergy

Platts-Mills made the revelation after examining allergic reactions to the cancer drug cetuximab, tracing the reactions to the sugar alpha-gal, an ingredient in the drug. Expanding on that, Platts-Mills and his team of researchers then made the connection to red meat by meticulously testing patients in his own clinic, eventually determining the cause of the allergy was the bite of the lone star tick.

In the process, Platts-Mills learned he actually suffered from the allergy he was in the process of discovering after breaking out in hives following a lamb dinner. He then used his own allergy to further his work.

“I’m covered in biopsy scars from doing research on myself,” he said.

Platts-Mills’ son, James, is a physician specializing in infectious disease at UVA and credits much of his father’s success to loving what he does and his attention to clinical practice.

“The red meat allergy story is a great example of that – it was a clinical observation that started the whole story, and he really applied a clinical lens to it to understand it,” he said. “As a clinician, what really sets him apart is how he talks to and connects with patients. He puts them at ease and just has this amazing level of comfort with them that I would say has influenced my own approach quite a bit.”

His father agrees, noting that believing patients could get anaphylaxis, a severe and potentially life-threatening allergic reaction, hours after eating meat was a huge jump to make when the reaction to peanuts or bee stings is almost instant.

“I don’t believe we would have understood the red meat story unless I was seeing the patients myself at the clinic and listening to them and truly believing what they were saying,” he said. “It’s a really good example of hearing something directly from a patient and then an utterly different patient tells a totally different story in essence but they’re saying the same thing. Ticks, red meat, allergy and a delay.”

***

Naturally, Platts-Mills accomplishments have not occurred without recognition.

In 2010, for more than 30 years of work research, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society, the United Kingdom’s national academy of science and the oldest scientific academy in the world, established in 1660. He is one of a small number of physicians ever elected and the first allergist.

He is also the recipient of two MERIT awards from the NIH for groundbreaking and important work, the first for his dust mite research and the second for his red meat allergy work.

But at a stage where many would be eyeing retirement, Platts-Mills remains focused on furthering his work, particularly exploring the possibility that there may be an undiagnosed national epidemic of meat sensitivity among people who show no symptoms of an allergy as their hearts are clogging up due to a tick bite.

And as ticks spread, especially in deer-heavy areas such as Charlottesville, so could the problem.

“We think it’s real,” he said. “I eat lamb and five hours later, I’m covered in hives. What has taken five hours to get there? And the only logical explanation is fat particles. … That’s where we’re going.”

That’s all the more reason, he says, why UVA needs a food allergy institute, combining both lab research and clinical work, he says.

“There are a very large number of families in the community who worry about food allergy and there are large numbers of people who worry about meat allergy. And if we’re right that there’s a connection to cardiovascular disease, that’s a very important issue,” he said. “And we need to create an institute to study it.

“Otherwise I’m going to have to move into cardiology,” he joked.